Follow @CNNPhotos on Twitter to join the conversation about photography.

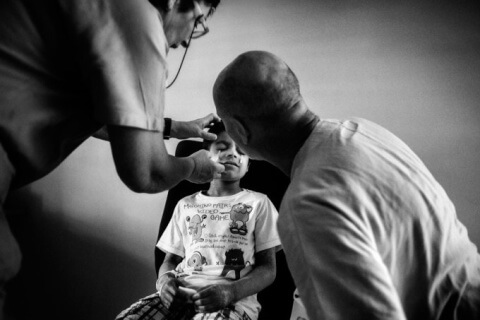

Luca Catalano Gonzaga’s project: The Witness Image: The Story of Alex

Witness Image: The Story of Alex

Living in shadows: A child’s rare disorder

By Ashley Strickland, CNN

CNN: Living in Shadows: A child’s rare disorder

(CNN) Alex Gentile has a very simple wish. The 8-year-old wants to run with his friends on the playground.

But because of a rare disease, he can’t play in the sunlight for very long.

Alex has X-linked reticulate pigmentary disorder with systematic manifestations — or what’s more commonly called XLPDR.

It’s so rare that there are only nine diagnosed cases worldwide.

Alex’s story is part of photographer Luca Catalano Gonzaga’s project, “Hopeful, ‘One of a Kind,’ ” that documents invisible diseases.

While many parents pride themselves on being vigilant, it’s imperative for Alex’s mother, Patrizia, to constantly monitor him.

“When he overheats, he risks his life,” she said. “A moment of negligence, a delay, and Alex dies.”

Days after she gave birth to Alex, her second child, she knew something was wrong. Alex was overly sensitive to light, cried constantly and suffered abdominal pain. He also had a respiratory infection at only 2 months old and was unable to sweat, so he easily overheated.

The conflicting symptoms confused doctors. It took three years of hospital visits and Internet research to figure out what might be wrong with Alex. He was finally diagnosed at age 3.

Online research also connected Patrizia with Dr. Andrew Zinn, a geneticist from Dallas, who studies XLPDR. The disorder was characterized in 1981 and largely affects males.

Alex has an ulcerated cornea and suffers from photophobia, meaning that he is incredibly sensitive to light and it can have a painful, blinding effect on him. At such a young age, he’s already losing his eyesight.

Alex’s body also lacks the ability to regulate his temperature, so he doesn’t sweat, cry or have as much saliva as the average person. Patrizia also has to monitor the temperature of his food so that it doesn’t increase his own. As he ages, Alex’s symptoms are only expected to worsen.

“There is no therapy — only eye drops, body creams, antibiotic for the infections and monitoring of internal and external temperature,” Patrizia said.

Gonzaga discovered the story of the Gentile family while studying the phenomenon of rare diseases. His project began in 2015 after reaching out to Patrizia and receiving her permission to tell Alex’s story.

Gonzaga visited them three times over the course of a year, capturing Alex’s everyday life through black-and-white images. He worried that color images would have detracted from the impact of Alex’s story.

But he was particularly struck by Patrizia’s strength and dedication to helping her son. A self-described stubborn, determined and proud woman, she gave up her job to take care of Alex as well as her daughter. Her husband does shift work to support the family, so he’s unable to help much with the children.

Patrizia also founded an association in 2012 to share what she knows of the disorder and raise awareness so that other families don’t have to endure their struggle alone.

“Alex’s family, in particular his mother Patrizia, taught me what ‘never give up’ really means — the importance to come out of the dark corner where one may fall when he feels alone and frightened,” Gonzaga said. “The smile of this family is contagious despite the difficulties and the extremely serious risks Alex takes when trying to live the life of any other child.”

“Alex’s family, in particular his mother Patrizia, taught me what ‘never give up’ really means — the importance to come out of the dark corner where one may fall when he feels alone and frightened,” Gonzaga said. “The smile of this family is contagious despite the difficulties and the extremely serious risks Alex takes when trying to live the life of any other child.”Patrizia tries to provide as normal of a life as possible for her son. He goes to school and has a supporting teacher and eye therapist to help him navigate any difficulties. But sometimes the other children remind him of the differences — that his skin looks different because of hyperpigmentation or that he’s slower and clumsier.

“Alex sees himself like any other child but he’s well aware of his conditions,” she said. “He loves life and is curious about everything. He (asks) a lot of questions; he’s a lively, friendly, kind and sensitive — but also proud and resolute — boy. But he’s noticing his own limitations. He can’t run or play like the other children. He lives at home while dreaming of open-air life. At this moment, he’s very angry.”

Gonzaga’s project of documenting Alex and his family is ongoing, and he plans to share their story in a book. He hopes that by pursuing humanitarian photojournalism and focusing his lens on “invisible people” will enable them to receive the help and support they need.

Gonzaga also wants the people who see “The Story of Alex” to have the same reaction he did: “A strong spur to take a greater interest in this problem, to systematize cooperation so that scientific research can invest in the development of innovative medicines, even if intended for only a small number of patients.

“Anyone suffering from a rare disease often receives a late and complex diagnosis. At best, it will take years.”

Luca Catalano Gonzaga is an Italian photographer based in Rome. He is a co-founder of Witness Image. You can follow the nonprofit on Facebook and Twitter.

Social media